Wrapping Up the 2020 St. Louis Film Festival

The Whitaker St. Louis International Film Festival recently completed its 2020 edition in its first-ever all-virtual format. With the future of theatrical screenings in limbo due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this alternative approach made it possible for the Festival to go forward, and it worked remarkably well, enabling viewers to screen a variety of films while remaining safe at home. As has been the case with other such events this year, this is a viable approach well worth considering for future programs, even without the threat of a pandemic. It makes it possible to offer the Festival’s films to a wider audience and provides flexible viewing conditions, benefits not necessarily available when presented exclusively in theatrical venues.

Because of this new format, I was able to screen a great number of films. In total, I watched 20 feature offerings, which are summarized below. One of these films was featured in a previous review, and some of the other offerings will subsequently be featured in expanded reviews on this site in the near future.

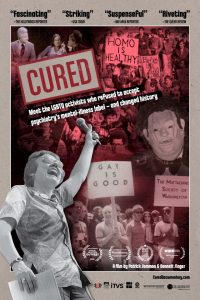

“Cured” (U.S.), (5/5) (*****)

How do you cure millions of supposedly mentally ill people overnight? By publicly proclaiming that their “affliction” of homosexuality isn’t an affliction at all. So it was in 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association dropped being gay from its official list of mental maladies. It was a hard-fought victory in the LGBTQ rights movement, one that’s meticulously detailed in this superb documentary. This film features a wealth of interviews with those who were on the front lines, as well as ample archive footage depicting the key moments in the effort to win over the hearts and minds of those who blindly accepted an assessment for which there was no scientific basis to back it up. In addition to chronicling this seminal development, the film is a fitting tribute to many unsung heroes in the LGBTQ rights movement, giving them the accolades they have long deserved. Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer’s fine offering is great viewing for those who believe in social justice, and it’s especially highly recommended for younger viewers in the LGBTQ community who may not – but need to – know their people’s history.

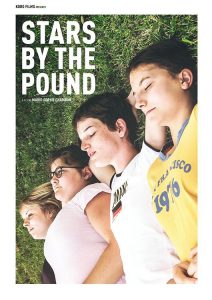

“Stars by the Pound” (“100 kilos d’étoiles”) (France), (5/5) (*****)

When an idealistic teen (Laure Duchêne) dreams of becoming an astronaut, she reaches for the stars. There’s just one problem – her chubby physique holds her down, both literally and figuratively. Nevertheless, this quest launches her on an unexpected journey of self-discovery as told through this positively delightful French charmer. Director Marie-Sophie Chambon’s debut feature may be a little commercial and a tad predictable, but so what – this release’s gentle humor, touching moments, inventive visuals and expertly cast ensemble make for an entertaining and uplifting time, the kind of movie we could use more of right now.

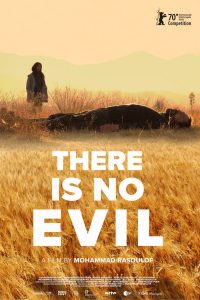

“There Is No Evil” (“Sheytan vojud nadarad”) (Iran/Germany/Czech Republic), (5/5) (*****)

“Remorse,” “regret” and “defiance” are words most of us would not readily associate with executioners, but they’re more than apropos when it comes to the characters in director Mohammad Rasoulof’s latest, “There Is No Evil.” This collection of four vignettes about the lives of executioners placed into situations bigger than themselves examines how these individuals cope with their circumstances, revealing feelings that those in this grim profession aren’t supposed to possess. While there are occasional pacing issues and a slight tendency for the filmmaker to wear his heart on his sleeve, these minor flaws are easily overlooked in the wake of the picture’s numerous other strengths. A surprisingly insightful offering.

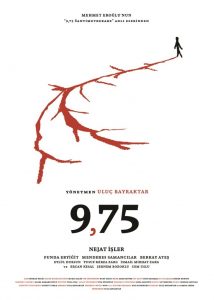

“9,75” (Turkey), (4/5) (****)

Where does reality leave off and fantasy take over? And what happens when those lines become blurred? Such are the dilemmas plaguing a former Turkish soldier and aspiring writer who’s battling PTSD and coping with a recent brain tumor diagnosis while trying to complete a highly personal novel before time runs out. This intense, emotive adaptation of author Mehmet Eroğlu’s 9,75 Santimetrekare (9.75 Square Centimeters) takes viewers through a range of emotions, backed by the performances of a fine ensemble, superb cinematography and an ethereal, atmospheric score. While the film could benefit from the deletion of extraneous material, and despite the fact that the blurring of the lines is, at times, a little too muddied for its own good, this debut feature from director Uluç Bayraktar nevertheless represents an impressive beginning to what is hopefully a bright career.

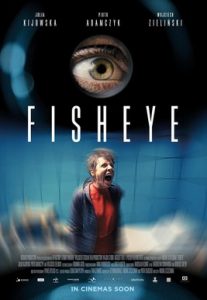

“Fisheye” (Poland), (4/5) (****)

When a brilliant research oncologist (Julia Kijowska) makes a huge breakthrough, she mysteriously disappears. Is someone out to steal her work? Or is something else afoot? As it turns out, she’s abducted and secluded in sound-proofed space immediately adjacent to her own apartment, but no one knows she’s there. During this captivity, she’s able to see and overhear developments in the lives of her nearest and dearest – as well as revelations about herself, clues to some of her own unexplained past behavior. But can she earn her freedom? And, if so, how, given that she doesn’t even know who kidnapped her? That’s the puzzle in director Michal Szczesniak’s debut feature, a psychological thriller that intriguingly operates on multiple levels. However, as engaging as this premise is, the picture begins to run out of story about two-thirds of the way through. It’s obvious the film is moving toward some sort of conclusion, but it becomes bogged down in tangents and padding that are likely to prompt viewers to demand “Get on with it already!” The makings of a great movie are here, especially Kijowska’s lead performance, but some much-needed shoring up is required to reach that goal.

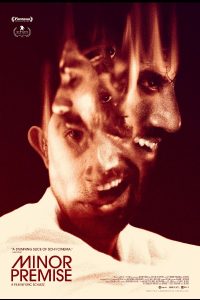

“Minor Premise” (U.S.), (4/5) (****)

How much does memory dictate our consciousness? Moreover, how much does our consciousness shape who we are? And is it possible to reshape our consciousness (and, hence, ourselves) by altering the memories that go into it? Such is the work of a research scientist (Sathya Sridharan) exploring technology designed to bring about such changes, using himself as the primary subject of his experiment. But, when things don’t go as planned, he opens a Pandora’s Box that’s difficult to again close. Filmmaker Eric Schultz’s debut feature echoes the works of director Christopher Nolan, as well as themes first raised in the sci-fi classic “Brainstorm” (1983), a hybrid sci-fi/smart horror/thriller that gets better with each passing frame. Although the film is a little too technical and needlessly cryptic in its first 30 minutes, it makes up for that once the story hits its stride, taking viewers on quite a ride all the way to its conclusion. Like many other offerings at this year’s film festivals, “Minor Premise” marks yet another premiere feature from a promising new talent – and one that intelligently kicks some ass in the process.

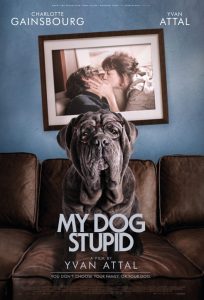

“My Dog Stupid” (“Mon Chien Stupide”) (France/Belgium), (4/5) (****)

This French comedy-drama about a once-successful author (Yvan Attal) whose life and career have stagnated after decades of marriage and fatherhood takes an unexpected and quirky turn when he impulsively adopts a big, dim-witted, perpetually randy, ever-slobbering dog who wanders into his garden and whose presence subsequently overturns the familiar routine he has long known but grown to despise. What starts off as a frothy farce gradually turns more introspective as the protagonist witnesses his life degenerating even further, a change that he initially believes he enjoys but soon comes to realize otherwise. With fine performances by actor-director Attal and Charlotte Gainsbourg, this often-hilarious yet thoughtful tale offers more than just another silly rambunctious dog movie, particularly when it comes to assessing our appreciation of what we have – and what we wish we had – as we get on in life. This delightful fare, reminiscent of early Woody Allen films but with its own distinctive spin, entertains from start to finish, even growing on viewers with multiple screenings, as it did for me in my second look. For a complete review, read more by clicking here.

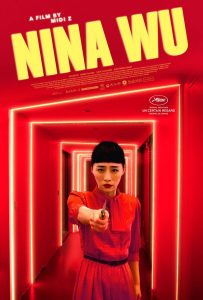

“Nina Wu” (“Zhou ren mi mi”) (Taiwan/Malaysia/Myanmar), (4/5) (****)

How far will one go to achieve success? That’s the question put to an aspiring Taiwanese actress (Ke-Xi Wu) who has been struggling for years for a breakthrough. But, now that a big opportunity has emerged, can she bring herself to do what’s asked of her? And can she do so if the requirements go against her own sensibilities? “Nina Wu” addresses these issues both through her own direct experience, as well as the images of her vivid dreams, bringing her face to face with herself, her internal conflicts and her ability to push her own limits, themes reminiscent of films like “Black Swan” (2010). Director Midi Z’s latest is never dull, providing viewers with a captivating tale through its many changes of mood, quirky humor and fine performances, even if it does begin to lose control of the room somewhat toward the end. Nevertheless, audiences will hang on every frame as they wonder where this evocative character study is going and how it will all turn out. While this may be one of the stranger offerings of recent years, its freshness, timeliness and distinctiveness are curiously and eminently satisfying.

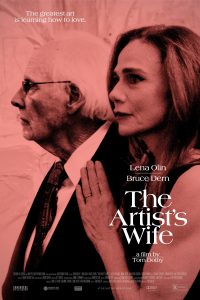

“The Artist’s Wife” (U.S.), (4/5) (****)

A moving, if sometimes slightly disjointed look at the life of a wife (Lena Olin) who gave up her pursuit to be an artist to support the painting career of her talented, famous and affluent but capricious and egotistical husband (Bruce Dern), a challenge made all the more difficult by the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, making him more volatile and unpredictable than ever. The dynamics of a woman torn between wanting to support her beloved and pull away to attend to her own needs are examined in multiple permutations, presenting a profile of a character frustrated while attempting to be conciliatory in multiple regards. The superb lead performances by Olin and Dern, backed by a fine supporting cast, really make this picture, helping director Tom Dolby’s effort shine, even when its sometimes-meandering narrative lets them down. A worthwhile candidate for awards season, especially in the acting categories.

“The Crossing” (“Flukten over grensen”) (Norway), (4/5) (****)

When the parents of a rural Norwegian family attempting to hide two Jewish children during World War II are taken into custody by authorities, it’s up to their own son and daughter (Bo Lindquist-Ellingsen, Anna Sofie Skarholt) to help the refugees (Samson Steine, Bianca Ghilardi-Hellsten) escape to the safety of nearby neutral Sweden. The quartet of youngsters thus embarks on a harrowing journey to stay ahead of their Nazi captors. While director Johanne Helgeland’s debut feature capably tells an inspiring and adventurous tale, the suspense level could certainly stand to be turned up a few notches to overcome the picture’s tendency toward formula and predictability, especially in the final act. The performances of the four young protagonists help to make up for this, however, something that will definitely appeal to peer-aged viewers. Overall, a well-crafted offering that could have benefitted from a bit more inventiveness but a worthwhile view nevertheless.

“The Dark Divide” (U.S.), (4/5) (****)

When a lepidopterist (David Cross) who’s an expert in his field doesn’t personally know what it’s like to go through the kind of transformation that all of his butterfly subjects experience, he sets out on a wilderness journey that provides him with that very metamorphosis. Filmmaker Tom Putnam’s fact-based story about the odyssey of Dr. Robert Pyle through one of the remotest wildlife areas in the country tells a tale encompassing a range of emotions, from laughter to tears to revelation, a picture highly reminiscent of films like director Jean-Marc Vallee’s “Wild” (2014). Though somewhat episodic at times, the overall narrative rings true to its mission and does so with beautiful cinematography, fine performances and an excellent score. When we all need to get on with our lives, stories like this give us a template to draw from so that we may all take flight.

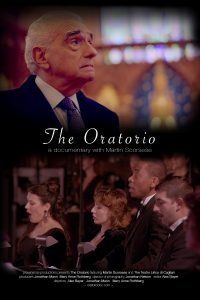

“The Oratorio” (U.S./Italy), (4/5) (****)

It’s amazing what a little culture can do. So it was in 1826 New York, when the first American performance of Italian-style operatic music was staged in the city’s Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, an oratorio arranged by Lorenzo da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist. This little-known event sparked a wave that impacted Gotham’s arts scene across the board, helping to make the city the center of American cultural life. In “The Oratorio,” directors Alex Bayer, Jonathan Mann and Mary Anne Rothberg document a present-day re-creation of that event, with commentary from the likes of Martin Scorsese and Jim Gaffigan, who call the cathedral their home parish. In addition to chronicling the current re-creation by the company of Italy’s Teatro Lirico Cagliari, the film details the original event, the life of its creator and the history of the cathedral, including its ongoing impact as a spiritual center for New York’s immigrant population. While this offering commendably presents material on a wide variety of subjects, its focus sometimes meanders a bit, and it could definitely benefit from more of what this picture is all about – the music. Nevertheless, “The Oratorio” is an otherwise-engaging and enlightening project that sheds light on a story whose influence has been far greater than its principals probably ever imagined – and one that deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

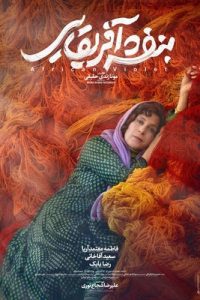

“African Violet” (“Banafsheh Afrighael”) (Iran), (3/5) (***)

Making up for past mistakes is certainly noble, especially when such gestures of compassion yield unexpectedly beneficial results. Such is the case in this Iranian domestic drama about a middle-aged woman (Fatemah Motamed-Aria) who takes in her elderly ex-husband (Reza Babak) when their children place him in a nursing home, an act of kindness that unwittingly unleashes an array of emotions between her and her second husband(Saeed Aghakhani). While this character study of the three principals has its heart in the right place, it tends to meander with the introduction of a variety of subplots that aren’t always fully resolved and sometimes seem like filler to compensate for a thin central narrative. Thankfully, director Mona Zandi Haghigi’s sophomore outing successfully avoids the trap of becoming melodramatic, but the finished product feels as though it could have used more substance and better focus to fully realize its potential.

“Coming Home Again” (U.S./South Korea), (3/5) (***)

I kept waiting for something to grab onto that would bring out the empathy in me in this tale of caregiving in the face of impending loss. Yet usually-reliable director Wayne Wang never really delivers on this point. Instead, the filmmaker gives us a sincere but ultimately thin, rote premise whose narrative is stretched to the limit, padded with interminably pregnant pauses, artfully photographed sequences (mostly of cooking) shot in stark silence and ample inconsequential dialogue that could easily have been cut. While the performances are generally impressive, much of what the ensemble has been asked to do comes up lacking in terms of evoking viewer engagement and bringing meaning to what’s going on in the hearts and minds of the characters. This offering feels like it could have given audiences so much more but, regrettably, fails to do so.

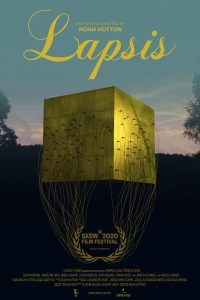

“Lapsis” (U.S.), (3/5) (***)

As a hybrid sci-fi/social satire offering, director Noah Hutton’s latest feature works well at the outset but sags in the middle and doesn’t quite stick the landing. The picture’s inventive premise, which examines the ennui, anger and frustration many of us feel about our collective mistrust of technology, a gamed financial system, big medicine, overly intrusive surveillance and condescending corporations, hits close to home (more so than many of us are probably comfortable with), but the flow of the narrative doesn’t tie the elements together as satisfactorily as one might like. It’s unfortunate that this production comes up short, because it starts out with so much promise that ultimately isn’t realized.

“Little Fish” (U.S./Canada), (3/5) (***)

In an age of epidemic memory loss, a married couple (Olivia Cooke, Jack O’Connell) very much in love with one another desperately seeks to hold on to their feelings and memories before they slip away – that is, if they can. So it is in director Chad Hartigan’s latest, “Little Fish,” a bittersweet love story set in the midst of a social and public health crisis. However, despite the film’s intriguing (and undeniably familiar) premise, the narrative ultimately seems thin, becoming somewhat circular as it progresses, as if stalling for time. And make sure the volume is tuned up for this one, too, given the picture’s poor sound quality. Regrettably, these shortcomings stymie the fine performances of Cooke and O’Connell and undercuts the picture’s other superb attributes, such as its lavish score and gorgeous cinematography. Indeed, if you’re looking for an offering that deals with subject matter like this (and better), check out Claire Carré’s “Embers” (2015) or the recently released Greek production “Apples” (2020) instead.

“Madre” (“Mother”) (Spain/France), (3/5) (***)

When a six-year-old mysteriously disappears, his mother (Marta Nieto) is left to pick up the pieces and work through her grief. But, a decade later, when an adolescent (Jules Porier) appears who reminds her of her missing son, she’s captivated but unsure how to react, especially when he makes overtures verging on inappropriate, potential kinship notwithstanding. Such is the stage set in director Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s latest, a compelling character study that starts out incredibly strong but loses its way the further one gets into the story, particularly in matters of pacing and narrative redundancy. That’s unfortunate given the strength of Nieto’s superb lead performance, along with the film’s atmospheric score and inventive cinematography. It’s certainly commendable that this offering tries to plumb new territory with its storyline, but the finished product could use some much-needed spit, polish and pruning to bring it up to speed.

“Citizens of the World” (“Lontano lontano”) (Italy), (2/5) (**)

While this Italian offering ultimately winds up delivering a pleasant, warm-fuzzy sentiment (although one that largely seems to emerge out of left field), writer-actor-director Gianni Di Gregorio’s latest takes a rather pedestrian path to that destination. What’s billed as a gentle comedy-drama about a trio of seniors (Di Gregorio, Ennio Fantastichini, Giorgio Colangeli) looking to escape the high cost of living in Rome by relocating abroad plays as a remarkably dull outing, with most scenes taking a purely functional approach and falling flat in the process. Sadly, what could have been a potentially raucous farce fails miserably, good intentions aside.

“Pacarrete” (Brazil), (2/5) (**)

As we age and life passes us by without attention, those of us who believe we still have something to say may try to attract that recognition by screaming for it at the tops of our lungs. So it is for an eccentric, egotistical retired ballet teacher (Marcelia Cartaxo) who wants to perform at her town’s bicentennial anniversary celebration. Despite a lack of interest from government officials, she insists on taking the stage and goes to any lengths to attempt to realize that goal. But, when the realities of aging catch up with her, what is she to do? Intriguing though that premise may be, this initially light and quirky comedy quickly becomes tiresome, primarily because the protagonist is not endearing, funny or even interesting – merely annoying. While the film makes up for this somewhat in its darker and more serious (though still overlong) second half, it’s not enough to save a project that just isn’t engaging enough to begin with. Director Allan Deberton’s offering plays like a picture whose script needed to go through a few more rewrites before being committed to celluloid. And that’s unfortunate given the message it apparently seeks to convey – that, just because we grow old, it doesn’t mean we should be casually cast aside, a prospect we’ll all come to face one day.

“Stardust” (U.K.), (1/5) (*)

The prospects for a picture about a historical figure don’t bode well when the opening frame unapologetically proclaims that what follows is mostly fiction. So it is with “Stardust,” an alleged “origin story” about a young David Bowie (Johnny Flynn) seeking to launch his career in America on a 1971 promotional tour plagued by problems, many of which originate with the rising rock star himself. But, given the opening disclaimer, how much of it is true? And, because of that, without further credible attribution, why should any of us care? Add to that a host of underdeveloped story threads, precious little music (including absolutely no Bowie compositions due to a rights issue), and, perhaps most critically, a cogent explanation of exactly how Bowie developed his alter-ego Ziggy Stardust, and you’ve got a mess of a movie that’s all over the map. To be sure, the capable performances of Flynn, Marc Maron and Jena Malone help to make up for these shortcomings somewhat. However, given the iconic talent that David Bowie was, he and his fans certainly deserve a better treatment of his life and accomplishments than what’s presented in director Gabriel Range’s sorely disappointing effort.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment