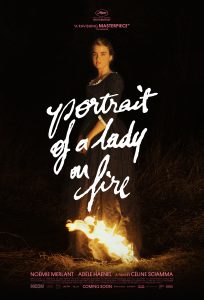

‘Lady on Fire’ fans the flames of forbidden romance

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”) (2019). Cast: Noémie Merlant, Adèle Haenel, Luàna Bajrami, Valeria Golino. Director: Céline Sciamma. Screenplay: Céline Sciamma. Web site. Trailer.

Asserting our right to openly proclaim who we love seems like a birthright we should all possess without hindrance. But, under some circumstances, doing so may be difficult, especially when we’re pressured to conform to the dictates of others. That’s unfortunately true even today, but it was far worse in the past, when social sanctions and familial obligations were much more restricting and pervasive, as illustrated in the French period piece drama, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”).

In 1760 France, Parisian artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is consigned to paint a wedding portrait under unusual circumstances. She journeys to an estate on the French seacoast, where she meets her client, a lonely middle-aged countess (Valeria Golino), who has asked the artist to paint a likeness of her daughter, Héloise (Adèle Haenel), whose hand has been promised in marriage to a Milanese gentleman she has never met. As straightforward as this might sound, however, the agreement comes with a number of strings attached. The most notable of these is that Marianne must paint the portrait from memory and observation, because Héloise refuses to pose for a project of this kind, a frustration that Marianne’s predecessor discovered and that eventually brought an end to his efforts at creating a finished work.

As an unwilling subject for a consigned wedding portrait, bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) seeks ways to get out of posing for the painting in the French period piece drama, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.

Héloise’s unwillingness to cooperate stems from the fact that she doesn’t want to get married in the first place, especially under arranged circumstances like these. In fact, she was not to be married off in the first place, a dubious distinction accorded to her sister, who died mysteriously and unexpectedly. With her sister’s untimely demise, Héloise was tapped to fulfill the family marital obligation, a commitment she loathed to honor, mainly because, prior to her unforeseen recent return home, she had been living a contented life in a convent, a place where she enjoyed the “equality” of being entirely among women. And now, by being forced into an undesirable arrangement, she’s not about to make matters easy for those coercing her into it.

Furthermore, the countess explains to Marianne that she’s not to reveal herself as a painter to her subject. Instead, she’s to pass herself off as a “companion” for Héloise, someone to spend time with her, accompanying her on walks and engaging in other genteel activities. It’s during these times together that Marianne is to gather her impressions of her subject, sketching them from memory when by herself or discreetly without Héloise’s knowledge when they’re together. Additional details about Héloise’s character, manner and qualities are to be quietly supplied by the estate’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), who clandestinely helps Marianne “fill in the blanks.” And, from these memories and observations, Marianne is expected to paint the portrait, all without her melancholy subject’s awareness.

At first, Héloise is reluctant to spend time in Marianne’s company, unsure of why this mysterious, newly arrived stranger has come to the estate. She acts as if she’s constantly on guard, suspicious that her mother may have planted a spy in her midst. She often responds brusquely when conversing with Marianne, seemingly ever on the defensive. She even seems to share some of the same self-sabotage qualities of her late sister. Yet, as time passes, Héloise discovers that Marianne shares many of the independent-minded ideas that she holds dearly. She even envies her new companion, particularly with regard to the fact that she appears to have choices in her life that she herself lacks. And, as time passes, they appear to be on the verge of becoming friends.

Parisian portrait artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, left) and her initially reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, right), grow unexpectedly close the more they work together in director Céline Sciamma’s latest offering, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.

When the time comes for Marianne’s big reveal approaches, she has misgivings about having deceived Héloise. She dreads the reaction she’ll get. Yet, much to her surprise, Marianne finds Héloise unexpectedly receptive, even when Marianne intentionally defaces the portrait as a ruse to paint a new one – and to get to spend more time with her new friend.

Needless to say, the countess is initially outraged by what has happened, calling Marianne a complete incompetent. But, when Héloise agrees to pose for the replacement painting, a startling decision that shocks the countess, she relents and allows Marianne to start over, convinced that a posed portrait could turn out even better than the one envisaged in her original plan. The artist thus gets a second chance to create the painting, to be finished by the time the countess returns from a trip.

In the countess’s absence, Marianne and Héloise begin work on the new portrait. Héloise feels a sense of liberation by posing for someone whom she considers an independent kindred spirit. They grow ever closer, developing a new level of intimacy that transcends friendship. They spend a glorious time together, their feelings of romance surfacing without hindrance or restriction.

But what’s to happen upon the return of the countess? Soon it will be time for Héloise to be joined in marriage. Will she go through with it? And what will happen to the torrid relationship that has been blossoming in recent weeks? With a woman on fire, it may be difficult if not impossible to extinguish the flames.

Parisian artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right), assigned to paint a wedding portrait exclusively from memory and observation, seeks input from her reluctant subject’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami, left), to help “fill in the blanks” about the bride-to-be in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.

At a time when women were genuinely treated as little more than chattel property, the frustrations they experienced were unbearable. The pervasive restrictions and limitations placed upon them kept them locked into incessant states of submission and subservience, with virtually no choices and almost no hope of escape from their circumstances save for the drastic measures apparently chosen by women like Héloise’s sister. And, as for Héloise, she was callously thrust into becoming a substitute for her sibling when the possibility of an obligation going unfulfilled arose, treated as little more than a commodity in a predetermined transaction. How demeaning.

Options for overcoming these confining conditions were almost nonexistent. Even beliefs in the possibility were scarce, though they were not inconceivable, even if difficult to achieve. But, to get the process moving, one at least had to be able to envision such a possibility, an outcome hatched through one’s thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality we experience.

In many regards, Héloise feels trapped, unable to extricate herself from these circumstances. She’s oppressed by seemingly everyone around her as they thoughtlessly and thoroughly dictate the conditions of her existence, a life that makes her time in the convent seem like an emancipated experience by comparison. She’s so disgusted by the prospect of what now awaits her that she seeks perpetual seclusion. She seems so despondent that her mother worries that she might befall a fate not unlike that of her sister, a concern that makes the countess grateful for Marianne’s presence to keep an eye on her daughter (especially for their walks along the jagged seacoast where her sibling’s lifeless body was found). She’s so convinced that there’s no escape that the only way she might be able to flee from her plight is to take matters into her own hands, an explanation for her self-sabotage tendencies.

An unexpected romance blossoms between portrait painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right) and her once-reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, left), in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.

But, much to her own surprise, Héloise finds that there may be hope for her when she becomes inspired by the example set by Marianne. Her comparatively unshackled friend provides her with a model for living life differently, a way of being more in line with what she craves. And, as this scenario unfolds, Héloise’s beliefs begin to change. Suddenly she finds herself facing the possibility that life could indeed be better than what she has typically been experiencing.

Several significant qualities accompany this unexpected change. For perhaps the first time in her life, Héloise experiences – and enjoys – the ecstasy that comes with feelings of personal liberation and independence, a rarity not only for her, but also for women in general of her time. And, as her feelings for Marianne emerge, Héloise’s passion for acting on these heartfelt instincts surfaces, a bold and impressive accomplishment given the forbidden nature of the relationship in which she engages. She no longer feels the need to deny herself what she believes makes her feel whole; the days of seeking self-imposed seclusion and solitude to cope with her circumstances become a thing of the past.

Taken together, Héloise’s embrace of the new beliefs behind these feelings and attributes represents the emergence of something even greater – her recognition, acceptance and nurturing of her authentic self, something she’s been restricted in expressing prior to this point. In fact, she’s so enthusiastic about the manifestation of her newfound self that she even inspires her inspiration – Marianne – enabling her to let her authentic self flower more profusely. At this point, Héloise is not the only lady on fire.

As Héloise becomes more aware of her authentic self, so, too, does Marianne, and in unexpected ways. For instance, it’s obvious Marianne has quite an ethical streak that runs through her being, and that’s why she feels so guilty about initially deceiving her new friend about her true self. Such behavior goes against her nature, and she’s pained by the fraud she’s perpetrated on Héloise. When she at last has an opportunity to allow her authentic self to come through, she’s thoroughly relieved. It enables her to be genuine, something that strengthens her bond with Héloise and allows their relationship to grow and prosper.

Once-secluded bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) becomes a lady on fire, literally and figuratively, after the onset of a torrid romance in director Céline Sciamma’s latest, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.

What’s perhaps most important about all this is that these circumstances allow Marianne and Héloise to serve as an inspiration to others similarly situated, a development that had to have been important at a time when such sources of support and encouragement were hard to come by. This is the conscious creation concept of value fulfillment at work, the notion that urges us to be our best, truest selves for the betterment of ourselves and those around us. This is not to suggest that Marianne and Héloise were ready to lead 18th Century versions of a women’s march or Pride parade, but they quietly added their consciousness and energetic input to movements that were quietly being birthed for future emergence. Initiatives like this have to get their start somewhere, even if their materialization doesn’t occur until sometime down the road, and we have individuals like Marianne and Héloise to thank for that.

While this film has a great deal to offer – gorgeous cinematography, exquisite staging and superb performances – this French period piece drama about forbidden romance simultaneously gets weighed down by such issues as sluggish pacing, an anticlimactic and often-predictable script, extraneous story threads, and an occasional lacking in gut-level believability. Director Céline Sciamma’s latest is indeed a joy to look at, and its content certainly constitutes an earnest, heartfelt attempt at a liberated lesbian manifesto. But, despite such apparent sincerity, the film sometimes comes across as somewhat tentative and restrained in going all-out for what it really wants to say (something of an irony for a picture with a title that includes the words “on fire” in it). To be sure, this is a fine piece of filmmaking in many regards, but rising to the level of “masterpiece” – a term that has been freely bandied about in describing this film – requires more than what’s served up here. The film is available for screening in various home media formats.

The foregoing criticisms aside, this 2019 release was widely recognized in a number of competitions and at film festivals. The picture was a nominee for best foreign language film in the Golden Globe, BAFTA, Critics Choice and Independent Spirit Award contests. In addition, the National Board of Review named the picture one of 2019’s top 5 foreign films. But the film’s greatest success came at the Cannes Film Festival, where it took top honors for best screenplay and won the Queer Palm Award for best gay cinema offering, along with a nomination for the Palme d’Or, the event’s highest honor.

It seems only natural that we should be free to be who we truly are, especially in matters of the heart. Yet there are so many instances, in romance and otherwise, where others try to control us (and we, regrettably, often allow them to). But, by being willing to live our lives as our authentic selves, and by empowering ourselves with beliefs to make that possible, we have an opportunity to fulfill that burning desire to be ourselves. And, if we’re able to make that happen, we truly have an opportunity to set our lives and our world ablaze with a glory unimaginable.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment