‘To Dust’ wrestles with expectations, obsession

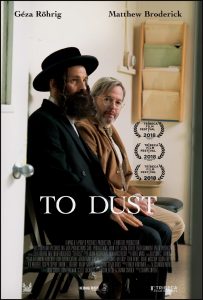

“To Dust” (2018 production, 2019 release). Cast: Géza Röhrig, Matthew Broderick, Leo Heller, Ziv Zaifman, Janet Sarno, Bern Cohen, Ben Hammer, Joseph Siprut, Marceline Hugot, Isabelle Phillips, Natalie Carter, Leanne Michelle Watson. Director: Shawn Snyder. Screenplay: Jason Begue and Shawn Snyder. Web site. Trailer.

We all have expectations about how life is supposed to unfold. In fact, we may feel so confident about them that we even take them for granted. But what happens when they don’t materialize as anticipated? That can easily make us uncomfortable, perhaps even unnerved, especially when there are high emotional stakes involved. And, when that process moves forward seemingly unchecked, we may even grow obsessive about these unmet expectations. So it is for a grieving widower when he comes up against what may (or may not) be happening with his deceased spouse in the edgy dark comedy, “To Dust,” available on DVD and video on demand.

When Hasidic cantor Shmuel (Géza Röhrig) loses his wife, Rivkah (Leanne Michelle Watson), to cancer at an early age, he’s devastated. Not only has he lost his beloved, but he’s also been left to raise two young sons, Noam (Leo Heller) and Moishe (Ziv Zaifman), as a single father. However, before long, those are not his only concerns; shortly after Rivkah’s burial, he begins having vivid and disturbing dreams about her transition from the world of flesh to the world of spirit, the process by which she turns “to dust.” He subsequently grows obsessed about the process of her body’s decomposition as worrisome thoughts cross his mind – How long is it supposed to take? Is her body’s breakdown progressing as it should in terms of timing and procedure? And, above all, will it end her suffering and lead to a proper transition to the life hereafter?

Those close to Shmuel grow concerned that he’s being overly morbid about all this, that he’s even running the risk of exceeding the stringent timeline his religion allows for grieving. To cope, he consults spiritual leaders (Bern Cohen, Ben Hammer) for guidance, but their answers don’t suit his needs. So, in an effort to get past this preoccupation, Shmuel concludes that he needs to better understand how the decomposition process works, a decision that starts him down a very slippery slope.

Worried that his deceased wife will transition from the world of flesh to the world of spirit on schedule, Hasidic cantor Shmuel (Géza Röhrig) becomes obsessed with understanding how the process works in the creepy but sublime dark comedy, “To Dust.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment.

Shmuel first consults an undertaker (Joseph Siprut), who rudely dismisses the cantor once he figures out that he’s not in the market for a casket or burial services. Frustrated, Shmuel then takes an even more radical step by seeking the advice of a man of science, a potentially blasphemous move that could easily get him expelled from his religion if discovered. Nevertheless, Shmuel needs answers, and he hopes to get them from Albert (Matthew Broderick), an oft-befuddled community college biology professor.

Shmuel shows up unannounced at Albert’s college, whereupon he unassumingly walks into his classroom and asks for help. Needless to say, Albert is perplexed at the mysterious visitor’s arrival, not having a clue who Shmuel is, why he’s there or what possessed the stranger to pick him for help. But, to one unaccustomed in the ways of science, Shmuel doesn’t see any distinction among its practitioners, so, in his mind, anyone who has any knowledge of the subject will do.

However, given that Shmuel’s inquiry carries as many theological considerations as it does scientific, Albert is convinced he can’t help him (not that he really wants to anyway). Nevertheless, Shmuel is insistent, so Albert begrudgingly sits down and begins explaining how the decomposition process works, the first step in what will become a long and complicated dark comedy of errors.

Put-upon community college biology professor Albert (Matthew Broderick) has an additional unexpected challenge to tackle when he’s approached with an unusual request from a Hasidic cantor in “To Dust.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment.

To say more would reveal too much, but suffice it to say that this unusual collaboration sparks a strange and comically macabre series of events involving an experiment to chart the decomposition rate of (of all things) a pig, a trip to a “human decomposition farm” and regular visits to a tranquil lakeside location where the cantor believes he’s able to commune with Rivkah’s spirit. Meanwhile, as all this unfolds, others look upon Shmuel and worry, including his sons, who have become convinced he’s in cahoots with a dybbuk; his spiritual leaders, who are concerned that the cantor has become incapable of carrying out his work; and his mother, Faigy (Janet Sarno), who quietly frets that he’s not getting on with his life to find a new wife, showing little interest in the prospective mate (Isabelle Phillips) she’s arranged for him to meet. And, through all this, there’s Albert, who’s increasingly put upon by Shmuel’s requests, including questionably ethical (and potentially illegal) incidents that could threaten his livelihood, career and personal freedom.

However, as this strange odyssey plays out, events unfold that provide surprisingly revelatory insights for all concerned, especially Shmuel. Truly meaningful developments emerge from unlikely events and individuals, providing answers where previously there were none: An impromptu road trip to Tennessee from their home in upstate New York proves remarkably telling, while a chance encounter with a security guard (Natalie Carter) ends up speaking volumes of once-hidden wisdom. And, in the process, the outwardly comical turns out to be richly sublime. Indeed, for those who doubt that the Lord works in mysterious ways, these episodes turn such skepticism on its head. But, then, as long as the unanswered questions finally receive responses, does it really matter where they come from or whether they follow prescribed expectations? After the kind of journey that Shmuel and Albert experience together, they might well say that it doesn’t matter a damn.

Shmuel’s loss is indeed sad. It’s patently obvious how much he loved Rivkah, and his worries about the well-being of her soul after her passing only make that loss that much more painful. He clearly needs to find closure so that he can make peace with her death and get on with his life. But, with relentlessly obsessive thoughts racing through his head and no readily available answers, he’s being tortured by his own mind, a process that carries on and seems to have no resolution. What is he to do?

Moishe (Ziv Zaifman, left) and Noam (Leo Heller, right), the young sons of a Hasidic cantor raising them as a single father, worry that their dad may be possessed by a dybbuk when he becomes obsessed with the after-death experience of his late wife in “To Dust.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment.

To a great degree, Shmuel is locked into these circumstances because of his beliefs, which, thanks to the philosophy of conscious creation, serve to shape the reality he experiences, for better or worse. Shmuel’s heavily bought into the beliefs of his religion, many of which follow rigidly prescribed dictates, established limitations that may – or may not – ultimately suit one’s needs or expectations. And, regardless of whether or not he genuinely believes in their validity, he’s expected to adhere to them to maintain his standing with his fellowship. But is that truly feasible?

This is not meant to denigrate one’s religion, but how can one be expected to observe such precepts if one has doubts about them? That’s the conundrum Shmuel quietly faces, especially when he begins having thoughts and dreams that prompt him to question what he’s supposed to accept without reservation. If he needs answers that his faith cannot provide, he must pursue other means to get them, and. if he cannot get past his grief in line within a stipulated timetable, then he must be allowed to give himself permission to move through that process at the pace that best suits him. And this must all happen even if it means risking his acceptance by his religious community.

At the same time, though, despite Shmuel’s courage to get answers in his own way, he still clings to many of the established beliefs he has long embraced. It’s as if he’s trying to dissect the mechanics behind these intangible notions in order to better understand them, despite prohibitions against doing so by the means he employs. He genuinely seems to want to believe in the fulfillment of the expectations he’s long believed in, even if their unfolding does not proceed according to what he has been taught to believe is supposed to happen.

Unfortunately, when faced with such seemingly conflicting circumstances, the result can be maddening, and that can lead to a perilously difficult outcome – obsession. Much of Shmuel’s behavior would seem to fit that pattern, one that grows progressively more consuming over time and that causes the concern expressed by his family and peers. And, once this sets in, it can lock one into an even more restrictive set of limiting beliefs, making escape increasingly difficult.

An experiment with, of all things, a pig leads to events spinning out of control for Shmuel, a Hasidic cantor (Géza Röhrig, right), and Albert, a community college biology professor (Matthew Broderick, left), in their quest to study human decomposition rates in the dark comedy, “To Dust.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment.

Several factors contribute to this. In part, Shmuel would seem to be engaged in some heavy-duty semi-conscious creation, an approach to the manifestation process that prevents its creator from recognizing that a desired aspiration has been materialized in principle, even if it doesn’t match the form that was anticipated. If Shmuel were to examine his circumstances realistically, he would discover that the breakdown of Rivkah’s corpse is indeed following its natural course, fulfilling the ultimate expectation, even if it’s not necessarily occurring in line with postulated projections. If he were to see this for what it is, he might be able to rest more easily.

Part of the reason why Shmuel may not be able to see this has to do with the role that doubt and fear can play in thwarting the manifestation process. As conscious creators are well aware, these factors can easily undermine how materializations unfold, largely because they are belief-based notions themselves that can contradict, and subsequently interfere with, the realization of anticipated outcomes. Since Shmuel’s thoughts are riddled with doubts and fears, is it any wonder, then, that his expectations might not achieve fulfillment? And, given that, is it any surprise that this development only leads to more doubt and fear that drives the progression of his obsessive behavior? It really becomes a vicious circle.

There are ways out, though, if Shmuel is willing to consider them. Thinking outside the box to consider the formation of beliefs that surpass limitations can go a long way to overcoming this. This process can be further enhanced in additional ways, such as paying attention to the synchronicities we encounter, those meaningful “coincidences” that seem to be so perfectly tailored to our needs that they can’t realistically be taken as random chance. It can also be aided by listening to our intuition, that quiet inner voice that speaks to us seemingly out of the blue and often doesn’t make sense yet ultimately proves to be spot on. To his credit, Shmuel takes these considerations to heart during the course of his journey, such as when he notices his ability to commune with Rivkah during his visits to the tranquil lakeside locale. Such interactions offer guidance that proves useful, not only in helping him retool his beliefs, but also in coming up with helpful resolutions to his issues.

Biology professor Albert (Matthew Broderick, left) and Hasidic cantor Shmuel (Géza Röhrig, right) find themselves in an increasingly questionable spot when they begin an experiment to measure human decomposition rates in the hilariously dark comedy, “To Dust.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment.

In the end, it’s possible to get past what holds us back, even in such matters as resolving profound grief. The process can be difficult enough to get through based just on the emotional devastation of what has happened, but it can become that much worse when we allow our minds to wander into territory that hinders resolution. But, by looking within and tapping into the beliefs driving all of this, we can at last achieve peace – and make it possible to move forward with our lives.

To be frank, some viewers may look upon “To Dust” as patently appalling or sacrilegious. Its dark humor, admittedly morose subject matter and lampooning of sacred principles might easily offend many. Indeed, there are many moments where viewers might find themselves laughing at things that they probably think they shouldn’t be chuckling about. But, in many ways, those elements are what makes this film work so effectively, especially when the humor is tinged with underlying insights that may not be apparent at first but that are quickly followed by a thoroughly pleasing aftertaste. This unlikely buddy flick grows increasingly hilarious with each passing episode, with Röhrig and Broderick serving up big, unexpected laughs that often prove deceptively profound and sweetly uplifting. This delicious little gem delivers more than what it superficially seems to offer, leaving viewers with good feelings, a warm glow, a tickled spirit and maybe even a new outlook on what comes after this life. For their efforts, screenwriters Jason Begue and Shawn Snyder earned an Independent Spirit Award nomination for their excellent, inspired script.

When we let our expectations get the better of us, they can eat us up more detrimentally than even the most aggressive microbes devouring a corpse. If they go unfulfilled, they can devastate us as they push us into obsessive behavior and frazzled states of mind. But we needn’t remain captives of our thoughts; we can break free and find peace of mind, provided we take the steps to do so – and as long as we take action before we turn to dust.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment