‘Maiden’ chronicles a sea change on the high seas

“Maiden” (2018 production, 2019 release). Cast: Tracy Edwards, Jo Gooding, Mikaela Von Koskull, Marie-Claude Kieffer Heys, Dawn Riley, Michèle Paret, Sally Creaser Hunter, Tanja Visser, Claire Russell, Amanda Swan Neal, Nancy Harris, Angela Heath, Sarah Davies, Jeni Mundy, Howard Gibbons, Skip Novak. Director: Alex Holmes. Web site. Trailer.

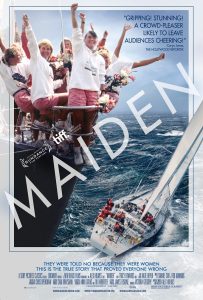

Fighting for recognition can grow tiresome, especially for those who have had to do so seemingly forever. Yet nothing is gained without making the effort, difficult and frustrating though that may be. Nevertheless, when the attempt succeeds, there’s a tremendous satisfaction that comes from it, not only in terms of realizing a goal, but also in setting a precedent that many may have thought could never be set. So it was for an ambitious crew of adventurers who took on a challenge of global proportions (and implications), as seen in the uplifting new documentary, “Maiden.”

In 1989, 24-year-old Tracy Edwards undertook a task that had never been tried before – fielding an all-female sailing crew for an entry in the Whitbread Round the World Race (now known as the Ocean Race). The arduous yachting event, which at the time covered more than 30,000 miles and was conducted in six legs over eight months, is the world’s longest race of any kind. And, given its sometimes-treacherous conditions, such as those of the South Ocean just north of Antarctica, it tests the mettle of even the hardiest of sailors.

In light of the foregoing, one can only imagine what the neophyte crew was up against when taking on this challenge, not just to be competitive but to even survive the ordeal, one that has had its share of fatalities. What’s more, in a sport that was heavily male dominated at the time, the all-female crew wasn’t taken seriously, often comically derided by chauvinistic journalists who saw the effort as a novelty, a side show or a warm, fuzzy human interest story.

With the backing of King Hussein of Jordan, the crew of the sailboat Maiden embarks on an epic global journey in the Whitbread Round the World Race as seen in the inspiring new documentary, “Maiden.” Photo courtesy of Tracy Edwards and Sony Pictures Classics.

These were the obstacles Edwards was up against when she began her campaign to launch her entry in the race. These hurdles were difficult enough in and of themselves, but, to make matters worse, they made it virtually impossible to find backers for this expensive proposition. And, if all this weren’t enough, those who knew Edwards had doubts about her ability to follow through on this enormous commitment, including her own mother, who didn’t hesitate to remind her once wild child daughter that she rarely saw anything through to completion.

So how did Edwards find herself wanting to take up such a daunting challenge? After an idyllic childhood with loving parents, Tracy experienced a series of upsets in the wake of the unexpected death of her father. When her mother remarried to an abusive stepfather, the teenager began a turbulent adolescence, eventually leaving home to be on her own. By her own admission, Tracy lived the life of a party girl, holding various short-term jobs and spending much of her time having fun. But, when she took a job as a hostess on a charter boat, her life took a radical turn.

Tracy discovered a love of boating, something that at last gave her a sense of direction. And, through a chance encounter with a VIP guest on one of her charter excursions – King Hussein of Jordan – she developed a lasting friendship with the monarch, who admired her drive and enthusiasm and urged her to pursue her dreams. In fact, the King would one day come to her rescue by providing the sought-after funding she needed to launch her entry in the Whitbread. With the monetary support she needed in hand, she was on her way, but many more challenges would lie ahead.

Crew members of the yacht Maiden (from left, Angela Heath, Mikaela Von Koskull, Michèle Paret, Tracy Edwards, Amanda Swan Neal) take on the challenges of the high seas as the first all-female team entered in the Whitbread Round the World Race as depicted in the engaging new documentary, “Maiden.” Photo courtesy of Tracy Edwards and Sony Pictures Classics.

To get the project afloat, Edwards needed two things: a boat and a crew, both of which proved to be challenges. For starters, yachts are expensive. And, in a sport where virtually all of the participants at the time were men, finding experienced sailing women was difficult. However, given Edwards’s resolve, she was determined to find what she needed, and, before long, with the ample guidance of land-side project manager Howard Gibbons, those needs were met.

The crew came together more easily than expected, almost as if it evolved into place. The members had varying degrees of experience, mostly from little to none, but they all had tremendous enthusiasm for the project, not just for the precedent it was setting, but also for the grand spirit of adventure that this undertaking represented. Edwards was also fortunate to land an experienced first mate, Marie-Claude Kieffer Heys.

As for the yacht, Edwards secured a used vessel that needed work – a lot of it. However, given her access to an enthusiastic team of refurbishers (i.e., the ship’s crew), she had much of the help she needed to make the boat seaworthy and, she hoped, competitive. After months of hard work, the craft was ready to embark on its global journey, an odyssey for which it was christened Maiden.

However, even with a crew in place and a boat ready to sail, the Maiden team still had problems to solve. The biggest challenge was a leadership conflict between Tracy and Marie-Claude, one that led to clashes and often left the crew unsure who was really in charge. It became apparent not long before the start of the race that this arrangement, as ideal as it may have looked on paper, was not going to work in practice, and so Marie-Claude was let go. While this change may have been good for morale, the first mate’s departure left a gaping hole in the crew, one that had to be filled if the effort were to go forward. With this being Tracy’s project, she stepped up to take Marie-Claude’s place, thus saddling herself with the dual role of skipper and first mate, a double dose of responsibility for someone who was not all that experienced at sailing in the first place.

And so, not long thereafter, it was time to shove off. The crew left the port of Southampton on September 2, 1989 on the initial leg of the race, crossing the Atlantic from the UK to Punta del Este, Uruguay. It was the first phase of five more to follow that took Maiden to Freemantle, Australia and Auckland, New Zealand before returning to Punta del Este and Southampton with a stop-off in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida in between. During the journey, the crew would face countless ordeals from howling winds and gargantuan waves to massive icebergs and life-threatening shipboard leaks. There was also the tragic news of the death of a crew member of another boat who was swept overboard and into the icy waters of the South Ocean. And, even with all this, the challenge of the race itself persistently lurked in the background, continuing to test the skills and competitive spirit of the crew even when their very survival was on the line.

Mikaela Von Koskull (left) and Jeni Mundy (right) steer the racing yacht Maiden through often-unpredictable waters in director Alex Holmes’s new documentary, “Maiden.” Photo courtesy of Tracy Edwards and Sony Pictures Classics.

These circumstances undoubtedly pushed the limits and abilities of the Maiden crew (as well as those of all the other entrants). The harshness of these conditions might easily prompt many to ask, “Why would anyone want to endure something like that?” However, it’s at times like these when one really gets to see what he or she is made of, and, for the crew of Maiden, they had much to prove, not only to a skeptical world, but also to themselves.

Pulling off a feat like this calls for a boatload of confidence, a self-assurance that it can indeed be accomplished. That’s where a fervent belief in one’s abilities and convictions comes into play, something made all the more possible by the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of these intangible building blocks. Were it not for the ardent belief in themselves, the crew of Maiden may have never left home port, let alone embarked on such an incredible journey, one whose demands were both literal and figurative.

A venture like this is not something one can approach casually. It takes vision, an ability to see what needs to be done and how to reach the sought-after goal. And, given that something like this had never been attempted before, there was no rule book for how the Maiden crew could arrive at its destination. Edwards and company had to devise a plan all their own, one that called for them to innovate, to push through limitations and break down supposedly insurmountable barriers, none of which would have happened if they didn’t believe they could.

Such envisioning factored into their plan in many ways. For example, in the run-up to the race, Edwards needed to work out the logistics of this effort, with funding arguably being the biggest challenge. She believed in the validity of her venture despite all of the rejections she received, a conviction that encouraged her to keep asking for support. Somewhere in her mind, she knew that someone would come through as long as she believed in the notion that it was OK to keep asking, a request that was finally fulfilled when she turned to her old friend, King Hussein.

The crew members of the sailboat Maiden (from left, Tracy Edwards, Mikaela Von Koskull, Michèle Paret (back turned), Jo Gooding, Claire Warren, Angela Heath, Sarah Davies, Amanda Swan Neal, Dawn Riley, Sally Hunter, Jeni Mundy, Tanja Visser) walk the deck of their vessel in the new documentary, “Maiden.” Photo courtesy of Tracy Edwards and Sony Pictures Classics.

That kind of belief conviction proved essential during the race itself as well. Given the harsh conditions the crew often faced, especially during the leg from Uruguay to Australia, Edwards and her shipmates were pushed to their limits. At times like that, their personal fortitude (and their personal belief in it) was severely tested, a time when survival was an even bigger reward than winning. Had it not been for such firmly rooted beliefs in themselves, the crew of Maiden may not have come through their ordeal safe and sound – or at all.

Of course, opportunities like this give each of us the chance to prove ourselves, to see what we’re truly capable of achieving. That can be especially significant when we’re attempting to take on the unprecedented, as the women of Maiden sought to do. But that need not be the sole motivation in such situations; sometimes tackling a quest in the spirit of the challenge itself, regardless of the impact of any ancillary considerations, is enough of an incentive, even if others have already accomplished the objective in question. The conditions of the Whitbread race, as previously noted, are difficult enough for anyone to take on, so surviving such a challenge could easily be satisfying in itself, even if other factors involved in the attempt are present. In that sense, the Maiden crew’s effort to conquer the Whitbread is truly inspiring, no matter what gender one might be.

None of this would have happened, however, were it not for the spirit of cooperation involved. Even though Maiden’s entry in the race was Edwards’s brainchild, and even though she carried the lion’s share of the burden in organizing the venture and formulating the team’s strategy, this was a collective effort, one in which each crew member made significant contributions, from the skipper all the way down to the ship’s cook. This is a prime example of co-creation at work, one in which all of the collaborators – both onshore and at sea – played a part in realizing the dream. By pooling the power of their beliefs, the women of Maiden realized the outcome they sought – to succeed at something that had never been attempted and that many skeptics openly scoffed at. Their story is truly one of inspiration, one that proves we can accomplish anything we try when we put our minds – and our beliefs – to it.

Although a little slow at the outset, this inspiring and entertaining documentary is more than just a laudatory exercise about taking on the untried. It’s also an engaging, beautifully photographed adventure saga about an arduous task that supremely tests one’s wits and endurance, regardless of gender or any other defining characteristic. This riveting, spellbinding tale depicts the triumphs and the perils of this venture, often characterized by an edge-of-your-seat quality, a trait rarely seen in documentaries. But, as expected, there is also the film’s pervasive uplifting message, one sure to inspire viewers, particularly young women looking for role models to spur them on to their own personal greatness. And, in that regard, there are few who can top what Tracy Edwards achieved.

The recent rise of the #MeToo movement has had a tremendous impact on society and its outlooks, changing how women are viewed and opening up opportunities that were not previously available. Yet, were it not for the accomplishments of courageous souls like Tracy Edwards and the crew of Maiden, there may not have been the foundation needed to build such an initiative. The achievements of the current movement’s forerunners deserve recognition, even years after the fact, for helping to launch the successes that are emerging now. Indeed, with the sails unfurled, there’s no telling where this voyage will take us.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment