An Ode to One of Filmdom’s Finest

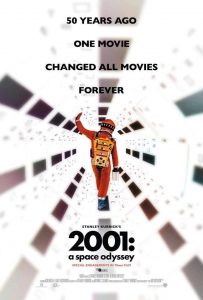

In recognition of the 50th anniversary of the release of Stanley Kubrick’s groundbreaking film, “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), a new 70-millimeter print of this cinematic icon is being released in theaters around the country. Produced from a true photochemical restoration printed off of the original camera negative, this new print is sharper and features better color than ever seen before. And, given how remarkably well this picture has held up since its original release, any improvement on it is a truly astounding accomplishment.

At the time of this celluloid enigma’s debut, few understood what Kubrick was trying to say through this film. It was – and still is – open to a range of interpretations, each equally valid in its own right. But, while some viewers may have been frustrated by this apparently intentional ambiguity, it also helps to characterize the picture for the masterpiece that it is. As one of the greatest motion pictures ever made, “2001” opened the door to a host of new cinematic experimentation, options that may not have been possible were it not for this unique offering and those who had the vision – and courage – to bring it to the public.

To this day, “2001” remains one of my all-time favorite films. In fact, my appreciation of this picture is so great that I included it as one of the featured entries in my debut book, Get the Picture?!: Conscious Creation Goes to the Movies (2007. 2014). And so, to honor this auspicious anniversary, I hereby present an updated version of my review from that title, my look at what I consider to be Kubrick’s greatest work.

The Next Frontier

“2001: A Space Odyssey”

Year of Release: 1968

Principal Cast: Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood,

William Sylvester, Douglas Rain (voice)

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke

Story: Arthur C. Clarke, The Sentinel (uncredited)

“Who am I?” and “Where did I come from?” Those are questions that theologians, scientists and even the exasperated parents of inquisitive youngsters have wrestled with for eons. But another question that’s just as vital, yet doesn’t get asked nearly as much, is, “Where are we going next?” The answer to that is as important to us as a species as it is to us as individuals. One film that attempts to provide some insight is the enigmatic sci-fi adventure, “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Even though we’ve long since passed the calendar year that’s part of this movie’s title, the picture itself is by no means outdated. In fact, in these days of shifting consciousness and changing paradigms, its message and mystique are perhaps more relevant than ever.

Although the film’s title makes the picture sound like a movie about space, it has more to do with evolution than astronomy. Director Stanley Kubrick’s cryptic yet poetic approach to the subject makes for a unique style of filmmaking, one that was decidedly way ahead of its time (and that baffled many viewers at the time of its original release).

In many ways, the plotline and characters are almost incidental to this picture. It’s really everybody’s story, that of the evolutionary journey of our species from the dawn of man to the time of our exploration of the heavens, first in our establishment of a base on the moon and then on a manned mission to Jupiter. The common thread linking all these seemingly disparate events is the spontaneous and unexplained appearance of a mysterious black monolith. The exact nature of this rectangular structure is never explained, but each of its appearances is immediately followed by some kind of significant leap in knowledge that helps further the evolution of the species.

Impressive as the monolith’s effects apparently are, however, one still can’t help but wonder what it is. Is it All That Is coming to us in physical form? A projection of the mass consciousness that somehow prompts us to greater self-understanding? A construct of an alien intelligence guiding our species’ progression toward ever-greater awareness? Or do none of these explanations suffice? And does it really matter what it is as long as forward movement results? All these questions are left ambiguously open, suggesting that perhaps the answers are bigger than our present level of comprehension is capable of assimilating but that each leap nevertheless takes us ever closer to discovering the truth.

The significance of this from the standpoint of conscious creation is that the flowering of our evolution is not unlike the constant state of becoming that author and conscious creation advocate Jane Roberts speaks of. That’s reflected in the narrative of the film, whose sequences are self-contained, with virtually no story line elements or characters that overlap or recur, except, of course, for the monolith. The mysterious structure acts like a bridge, linking the sequences, and a catalyst, sparking into existence whatever follows next.

Given that, one might understandably wonder how the monolith itself figures into the conscious creation equation. That’s difficult to answer, especially since its precise nature and function are never delineated. I can’t speak to this from personal experience, either, for I’ve never seen a giant black rectangle appear before me when I’ve been on the verge of a eureka moment. However, given the conditions under which the monolith appears in the film, it always seems to show up when man has been on the brink of needing to make one of those major leaps in cognition. So, if we’re all conscious creators by nature, then one could speculate that the characters who are on those thresholds of evolutionary advances are the ones who summon forth the monolith (and whatever powers its holds or represents) to help facilitate these changes.

In many instances, the needs for advancement depicted in the movie are driven by survival considerations, so one could argue that the monolith is an abstract embodiment of the belief that “necessity is the mother of invention.” Why these characters would feel compelled to manifest a physical symbol of this at all, let alone in the specific form depicted herein, is a bit of a mystery, but perhaps it’s simply meant to be an outward reminder of our innate materialization capabilities, serving like the proverbial string tied around one’s finger. But why an enigmatic black rectangle? Your guess is as good as mine. While a string around the finger might be eminently more manageable from a practicality standpoint, it would also make for far less engaging filmmaking.

Evolution is apparent in a number of ways in the film. It’s most obvious in terms of our physical appearance, first as apes and later as Homo sapiens (and beyond). It’s also present in our physical locations, first as earthbound primates and later as humans soaring toward the stars. It’s even reflected in the complexity of our physical creations, progressing from crude levels to ever-increasing degrees of sophistication, in everything from our tools to the meals we consume. It might be tempting to assume that it’s all possible thanks to a mysterious black rectangle, yet it’s we who manifest the creations that result after its appearance. Maybe the monolith is doing nothing more than trying to remind us, like Glinda in “The Wizard of Oz” (1939), that we’re the ones with the power to create the realities we experience. Armed with that knowledge, it’s exciting to envision the possibilities for what comes next.

Kubrick was clearly at the top of his game with this masterpiece, deservedly earning an Academy Award for the production’s magnificent special effects. Viewing “2001” is more like watching a moving painting than a moving picture. The narrative unfolds before us slowly, like the pace of evolution itself, with its dazzling cinematography and spectacular visual effects shouldering much of the responsibility for telling the story. Backing all this is a classical-based soundtrack that features compositions as whimsical as the Johann Strauss waltz, On the Beautiful Blue Danube, and as inspiring as the introduction to the Richard Strauss tone poem, Also Sprach Zarathustra, a fanfare that has become virtually synonymous with the movie. In addition to Kubrick’s Oscar, the picture earned three more nominations, including nods for best director and best original screenplay.

“2001: A Space Odyssey” is, in many ways, the ultimate road trip film, showing us where we came from, where we’re going and who we’ve been all along the way. The one trait that links all the stops along that path is the sense of awakening that arises within each of us with our passage through each stage of the journey. It affirms, for me at least, the idea that, if you’ve liked what you’ve seen so far, wait till you see what’s next. And that’s something to look forward to.

Copyright © 2007, 2014, 2018, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment