“The New Bauhaus” (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Interviews: Olafur Eliasson, Elizabeth Siegel, Joyce Tsai, Robin Schuldenfrei, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Barbara Kasten. Archive Material: László Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius. Director: Alysa Nahmias. Screenplay: Alysa Nahmias and Miranda Yousef. Web site. Trailer.

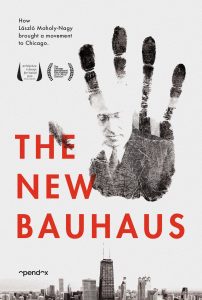

A Chinese fortune cookie I once cracked open imparted a simple but inspiring message, “There is no greater joy than creation.” Those words have stayed with me for years, and I’m always moved when I see comparable sentiments expressed through other means. And, in that vein, a recently released film echoes that notion through a portrait of an individual whose calling epitomizes that very idea, the central figure profiled in the engaging new documentary, “The New Bauhaus,” available for first-run online streaming.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) isn’t exactly a household name, though there are many who contend that it should be. As one of the most influential yet least known figures in 20th Century art and design, Moholy-Nagy’s imprint can be found in a wide array of artworks, as well as the design of many everyday consumer goods. That’s quite a range for any one person, but not all of these creations come directly from his hand; many are the creations of the students he taught and the peers he influenced over the years. Yet the inspiration, in either case, stems from a brilliant, if underappreciated visionary who accomplished more individually in his scant 51 years than groups of collaboratives produce in their entire lifetimes.

Visionary artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy in a 1925 self-portrait. Photo by László Moholy-Nagy, © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Born in Hungary in 1895 to a largely dysfunctional family, the young László was shuttled off to be raised by extended relatives. Given these conditions, he quickly learned how to look after himself, taking the initiative to attend to his own needs. By his late teens he moved to Budapest and then Berlin, becoming involved in a variety of cutting-edge technology and modern art ventures. He developed a reputation for his innovative works, and, in 1923, was invited to join the faculty of the Bauhaus, a German art and architecture institute known for its leading-edge work. It was quite a coup for a bright young mind full of ideas who had no formal training.

With the rise of the Nazi party, however, conditions changed radically. The Reich’s disapproval of modernist artworks – what came to be known as “degenerate art” – made it difficult for Moholy-Nagy and his peers to get their work into circulation, let alone accepted. What’s more, new laws were enacted restricting the employment of foreigners within Germany, hindering the Hungarian artist to continue working there. He soon left for the Netherlands and then England, though neither location suited him. So, when he had an opportunity to relocate to the U.S. in the 1930s, he jumped at the chance.

Moholy-Nagy landed in the bustling city of Chicago, a metropolis whose freewheeling spirit and boundless energy intrigued him, a perfect fit for an artist seeking to explore his creative leanings and make a name for himself. He found that opportunity in 1937, when the Association of Arts & Industries sought to establish a new school based on the Bauhaus model, and the organization reached out to Moholy-Nagy to head up the venture. Before long, the New Bauhaus was born.

An exterior shot of the New Bauhaus school in Chicago, 1938. Photo courtesy of Opendox.

In launching this effort, Moholy-Nagy had an ambitious agenda in mind. He sought to create an educational environment that went beyond mere vocational training in design. Instead, Moholy-Nagy envisioned an institution where students could learn the mechanics of creativity, becoming immersed in discovering how to fuse art, design and technology in new and creative ways. The intent was to go beyond just coming up with finished products; it was about learning how raw materials could be fashioned in ways that revealed their innate properties, especially discovering qualities and attributes that may never have been dreamed of before, all in the hope of developing goods that were both aesthetically pleasing and successfully fulfilled practical objectives that made life better, easier and more enjoyable for their end users.

Moholy-Nagy’s experiment may have been noble, but it was something of a flop. Many of the students didn’t grasp what the founder was striving for. And the school’s backers were disappointed that this new venture wasn’t yielding the kinds of outcomes they sought. After a year, the New Bauhaus was history, and Moholy-Nagy was looking for his next opportunity.

With the generous backing of Chicago-based Container Corporation of America, a company known for its support of the arts both in its advertising and corporate culture, Moholy-Nagy subsequently launched his own institution, the School of Design in Chicago (later renamed the Institute of Design) in 1939. Given such a sympathetic sponsor to bankroll his efforts, Moholy-Nagy was free to pursue the establishment of the kind of school he wanted to create. And, this time, the students took to it with tremendous optimism, joy and enthusiasm. They relished the creative freedom this environment afforded, and they happily went about their pursuits, no matter how demanding the work may have been.

Taking a hands-on instruction to his teaching at the School of Design, László Moholy-Nagy worked directly with his students in encouraging them to find their own creative voices. Photo © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Moholy-Nagy became a celebrity of sorts through this enterprise, his school often attracting noted artists who made appearances as guest lecturers and faculty, frequently taking no fees for their contributions. One of the most noteworthy was visionary Buckminster Fuller, who spoke before rapt audiences of design students eager to soak up whatever wisdom and insights he had to offer.

Continuing the approach he used at the New Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy encouraged his students to find their own creative voices. He wanted them to understand the rudimentary aspects of design and material qualities and how they could be transformed into art, regardless of the finished product in question. In essence, this provided students with a creative template or framework from which to operate, showing them that their approach to their efforts was ultimately more important than what resulted from it.

Nonetheless, truly inventive creations came out of these hypothetical endeavors, items that may not have been envisioned were it not for the innovative approach employed in coming up with them. For instance, this approach led to artistically appealing yet practical applications in the area of product design ergonomics. The Dove soap bar, with its distinctive curved shape that perfectly fits both a soap dish and a user’s palm, is a prime example of a consumer good that employed this design technique and became a best seller in the process. The same is true of the whimsical and wildly popular bear-shaped honey dispensers that can be found on many American breakfast tables. And then there’s the clam shell-shaped telephone, which didn’t catch on at the time it was designed but subsequently inspired the look of many handsets to come along in later years.

Moholy-Nagy’s influence touched the works of artists in many other areas, too. For example, he inspired many graphic artists, such as those who went on to design the initial issues of Playboy magazine, the psychedelic advertising materials used by 7 Up in the 1960s and album covers for the Rolling Stones. He even had an impact on those in the movie industry, including the designer of the inventive cinematic montages featured in the opening credits of the James Bond films.

When raw materials were in short supply, such as during World War II, Moholy-Nagy encouraged his students to experiment with alternatives, like wood instead of metal, to determine their viability in design efforts. Photo © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Perhaps one of Moholy-Nagy’s greatest accomplishments was changing how we view photography. At the time he worked with it, photography was seen as a technology, nothing more. However, by employing it in new and different ways, he transformed it into a serious art form, a designation it previously hadn’t enjoyed. Today we take such a notion for granted, but, were it not for Moholy-Nagy’s efforts, that outcome may have never resulted. But then that was typical of how he approached his craft, looking for ways to fuse elements and disciplines in ways that hadn’t been attempted before – and forever changing our world, our perceptions and our art in the process.

Sadly, Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia at age 51 in 1946. Some would say he left us far too soon, but, as his daughter Hattula observes in the film, he produced a wealth of material in an array of milieus during the time he was here. The impact he had on the art world, both seriously and commercially, went underappreciated for decades, but, thanks to recent museum exhibitions and this film, his contributions are finally beginning to receive their just due.

What’s arguably even more important, though, are the insights he imparted about the creative process and how it can be applied to so many assorted endeavors, including those that go beyond what we typically associate with the concept of art. Moholy-Nagy placed as much value on the means and methods by which we create as on what results from them, an idea that was revolutionary for the time (and not always readily accepted). Nevertheless, he firmly believed in what he was doing and drew upon those notions in manifesting his works, products of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these resources for materializing our existence. And what a reality he created, one that keeps on manifesting today, years after his death.

Art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist reads excerpts from the writings of artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy in the engaging new documentary about the prolific visionary, “The New Bauhaus.” Photo by Petter Ringbom, courtesy of Opendox.

Even if Moholy-Nagy never heard of this philosophy, he clearly had a good handle on its principles. A big part of his success is attributable to his focus on beliefs related to the inherent means for bringing all this about. In many instances, we tend to place so much emphasis on the end result that we lose sight of how we get there. Yet the process is what makes the outcome possible, so, if we hope to arrive where we want to be, we should give due consideration to the journey and not just the destination, for the trip will determine the form we end up with.

The beliefs that go into the creative process not only show us the direction to take, but they may also help us to imbue the outcome with qualities that we might not have otherwise envisioned. Moholy-Nagy believed that what we create should both fulfill the sought-after needs and provide end users with attributes that make their lives more useful and satisfying. Those aspects of a creation may not be apparent at the outset, but they could well emerge as the design process unfolds, revealing themselves as the manifestation gradually comes into being. Indeed, if one were to wonder how a proverbial better mousetrap might arise, this approach to building it would likely reveal how.

This approach proved valuable to Moholy-Nagy not only in devising his finished works, but also in terms of how he ran his school. For example, during World War II, when finances and materials became more scarce, he had to get creative to come up with new ways to acquire both in adequate supplies. Where money was concerned, for instance, he attracted funding by introducing curricula with practical applications, such as camouflage design. He sought to recruit students (and their tuition money), along with additional funding support, to investigate the means for projects like hiding large buildings and even concealing the entire Chicago lakefront. On the materials side, with metal hard to come by because of the war effort, he looked at alternate resources to work with. Consequently, he and his students began experimenting with wood in ways never thought of, such as using it to provide the support mechanisms in bedding.

To succeed at envelope-pushing endeavors like this, we need to push past the limitations in our beliefs that hold us back. This is positively essential for projects where creativity is a core element of the undertaking, because standard approaches aren’t likely to yield anything new, different or innovative. Fortunately, limitations don’t even appear to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s thinking; he stridently forged ahead, apparently not giving a second thought to the restraints of convention. And, for both his benefit (and ours), it’s good that they weren’t part of his process; we can only guess what imaginative manifestations would be missing from our reality today if it had been otherwise.

Thanks to events like museum exhibitions, the work of Moholy-Nagy is finally starting to receive the recognition it deserves, as detailed in the new documentary, “The New Bauhaus,” available for first-run online streaming. Photo by Petter Ringbom, courtesy of Opendox.

Thankfully, this approach to the creative process appears to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s value fulfillment, the conscious creation principle associated with being our best, truest selves for the betterment of our being and that of others. His influence was (and still is) far-reaching, resulting in many creative finished works to be enjoyed, both aesthetically and commercially, as well as inspiring the output of generations of fellow kindred spirits who have since walked in his footsteps. That’s quite a legacy, one whose impact continues to unfold to this day and is likely to continue doing so on into the future.

“The New Bauhaus” is a fitting cinematic tribute to an underrated artist and his work, featuring plenty of examples of his art and that of those he influenced. The film’s extensive archive material shows rare footage of Europe in the days before his immigration, as well as ample still photos from the subject’s time at the New Bauhaus and the School of Design. A wealth of expert commentary is provided by Moholy-Nagy’s daughter, Hattula, along with observations from educators, art curators, historians and former students and quotes from Moholy-Nagy’s writings read by art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist. Aspects of the protagonist’s life chronology could be a little better organized, but the overall portrait painted here provides an in-depth look at the life of someone influential but largely unknown.

As the experience of Moholy-Nagy and his followers illustrates, there is tremendous power and joy in acts of creation. They can take a plethora of forms, too, unfathomably greater than even the phenomenally prolific output of the New Bauhaus and School of Design students and faculty. That in itself should be good cause for the optimism, joy and enthusiasm that came to characterize the attitudes of those enrolled in these remarkable institutions, serving as an uplifting example to the rest of us as we undertake all of our creative endeavors, whether we’re attempting something as ambitious as painting a mural – or simply cooking dinner.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

‘The New Bauhaus’ dissects the creative process

“The New Bauhaus” (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Interviews: Olafur Eliasson, Elizabeth Siegel, Joyce Tsai, Robin Schuldenfrei, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Barbara Kasten. Archive Material: László Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius. Director: Alysa Nahmias. Screenplay: Alysa Nahmias and Miranda Yousef. Web site. Trailer.

A Chinese fortune cookie I once cracked open imparted a simple but inspiring message, “There is no greater joy than creation.” Those words have stayed with me for years, and I’m always moved when I see comparable sentiments expressed through other means. And, in that vein, a recently released film echoes that notion through a portrait of an individual whose calling epitomizes that very idea, the central figure profiled in the engaging new documentary, “The New Bauhaus,” available for first-run online streaming.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) isn’t exactly a household name, though there are many who contend that it should be. As one of the most influential yet least known figures in 20th Century art and design, Moholy-Nagy’s imprint can be found in a wide array of artworks, as well as the design of many everyday consumer goods. That’s quite a range for any one person, but not all of these creations come directly from his hand; many are the creations of the students he taught and the peers he influenced over the years. Yet the inspiration, in either case, stems from a brilliant, if underappreciated visionary who accomplished more individually in his scant 51 years than groups of collaboratives produce in their entire lifetimes.

Visionary artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy in a 1925 self-portrait. Photo by László Moholy-Nagy, © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Born in Hungary in 1895 to a largely dysfunctional family, the young László was shuttled off to be raised by extended relatives. Given these conditions, he quickly learned how to look after himself, taking the initiative to attend to his own needs. By his late teens he moved to Budapest and then Berlin, becoming involved in a variety of cutting-edge technology and modern art ventures. He developed a reputation for his innovative works, and, in 1923, was invited to join the faculty of the Bauhaus, a German art and architecture institute known for its leading-edge work. It was quite a coup for a bright young mind full of ideas who had no formal training.

With the rise of the Nazi party, however, conditions changed radically. The Reich’s disapproval of modernist artworks – what came to be known as “degenerate art” – made it difficult for Moholy-Nagy and his peers to get their work into circulation, let alone accepted. What’s more, new laws were enacted restricting the employment of foreigners within Germany, hindering the Hungarian artist to continue working there. He soon left for the Netherlands and then England, though neither location suited him. So, when he had an opportunity to relocate to the U.S. in the 1930s, he jumped at the chance.

Moholy-Nagy landed in the bustling city of Chicago, a metropolis whose freewheeling spirit and boundless energy intrigued him, a perfect fit for an artist seeking to explore his creative leanings and make a name for himself. He found that opportunity in 1937, when the Association of Arts & Industries sought to establish a new school based on the Bauhaus model, and the organization reached out to Moholy-Nagy to head up the venture. Before long, the New Bauhaus was born.

An exterior shot of the New Bauhaus school in Chicago, 1938. Photo courtesy of Opendox.

In launching this effort, Moholy-Nagy had an ambitious agenda in mind. He sought to create an educational environment that went beyond mere vocational training in design. Instead, Moholy-Nagy envisioned an institution where students could learn the mechanics of creativity, becoming immersed in discovering how to fuse art, design and technology in new and creative ways. The intent was to go beyond just coming up with finished products; it was about learning how raw materials could be fashioned in ways that revealed their innate properties, especially discovering qualities and attributes that may never have been dreamed of before, all in the hope of developing goods that were both aesthetically pleasing and successfully fulfilled practical objectives that made life better, easier and more enjoyable for their end users.

Moholy-Nagy’s experiment may have been noble, but it was something of a flop. Many of the students didn’t grasp what the founder was striving for. And the school’s backers were disappointed that this new venture wasn’t yielding the kinds of outcomes they sought. After a year, the New Bauhaus was history, and Moholy-Nagy was looking for his next opportunity.

With the generous backing of Chicago-based Container Corporation of America, a company known for its support of the arts both in its advertising and corporate culture, Moholy-Nagy subsequently launched his own institution, the School of Design in Chicago (later renamed the Institute of Design) in 1939. Given such a sympathetic sponsor to bankroll his efforts, Moholy-Nagy was free to pursue the establishment of the kind of school he wanted to create. And, this time, the students took to it with tremendous optimism, joy and enthusiasm. They relished the creative freedom this environment afforded, and they happily went about their pursuits, no matter how demanding the work may have been.

Taking a hands-on instruction to his teaching at the School of Design, László Moholy-Nagy worked directly with his students in encouraging them to find their own creative voices. Photo © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Moholy-Nagy became a celebrity of sorts through this enterprise, his school often attracting noted artists who made appearances as guest lecturers and faculty, frequently taking no fees for their contributions. One of the most noteworthy was visionary Buckminster Fuller, who spoke before rapt audiences of design students eager to soak up whatever wisdom and insights he had to offer.

Continuing the approach he used at the New Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy encouraged his students to find their own creative voices. He wanted them to understand the rudimentary aspects of design and material qualities and how they could be transformed into art, regardless of the finished product in question. In essence, this provided students with a creative template or framework from which to operate, showing them that their approach to their efforts was ultimately more important than what resulted from it.

Nonetheless, truly inventive creations came out of these hypothetical endeavors, items that may not have been envisioned were it not for the innovative approach employed in coming up with them. For instance, this approach led to artistically appealing yet practical applications in the area of product design ergonomics. The Dove soap bar, with its distinctive curved shape that perfectly fits both a soap dish and a user’s palm, is a prime example of a consumer good that employed this design technique and became a best seller in the process. The same is true of the whimsical and wildly popular bear-shaped honey dispensers that can be found on many American breakfast tables. And then there’s the clam shell-shaped telephone, which didn’t catch on at the time it was designed but subsequently inspired the look of many handsets to come along in later years.

Moholy-Nagy’s influence touched the works of artists in many other areas, too. For example, he inspired many graphic artists, such as those who went on to design the initial issues of Playboy magazine, the psychedelic advertising materials used by 7 Up in the 1960s and album covers for the Rolling Stones. He even had an impact on those in the movie industry, including the designer of the inventive cinematic montages featured in the opening credits of the James Bond films.

When raw materials were in short supply, such as during World War II, Moholy-Nagy encouraged his students to experiment with alternatives, like wood instead of metal, to determine their viability in design efforts. Photo © Moholy-Nagy Foundation, courtesy of Opendox.

Perhaps one of Moholy-Nagy’s greatest accomplishments was changing how we view photography. At the time he worked with it, photography was seen as a technology, nothing more. However, by employing it in new and different ways, he transformed it into a serious art form, a designation it previously hadn’t enjoyed. Today we take such a notion for granted, but, were it not for Moholy-Nagy’s efforts, that outcome may have never resulted. But then that was typical of how he approached his craft, looking for ways to fuse elements and disciplines in ways that hadn’t been attempted before – and forever changing our world, our perceptions and our art in the process.

Sadly, Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia at age 51 in 1946. Some would say he left us far too soon, but, as his daughter Hattula observes in the film, he produced a wealth of material in an array of milieus during the time he was here. The impact he had on the art world, both seriously and commercially, went underappreciated for decades, but, thanks to recent museum exhibitions and this film, his contributions are finally beginning to receive their just due.

What’s arguably even more important, though, are the insights he imparted about the creative process and how it can be applied to so many assorted endeavors, including those that go beyond what we typically associate with the concept of art. Moholy-Nagy placed as much value on the means and methods by which we create as on what results from them, an idea that was revolutionary for the time (and not always readily accepted). Nevertheless, he firmly believed in what he was doing and drew upon those notions in manifesting his works, products of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these resources for materializing our existence. And what a reality he created, one that keeps on manifesting today, years after his death.

Art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist reads excerpts from the writings of artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy in the engaging new documentary about the prolific visionary, “The New Bauhaus.” Photo by Petter Ringbom, courtesy of Opendox.

Even if Moholy-Nagy never heard of this philosophy, he clearly had a good handle on its principles. A big part of his success is attributable to his focus on beliefs related to the inherent means for bringing all this about. In many instances, we tend to place so much emphasis on the end result that we lose sight of how we get there. Yet the process is what makes the outcome possible, so, if we hope to arrive where we want to be, we should give due consideration to the journey and not just the destination, for the trip will determine the form we end up with.

The beliefs that go into the creative process not only show us the direction to take, but they may also help us to imbue the outcome with qualities that we might not have otherwise envisioned. Moholy-Nagy believed that what we create should both fulfill the sought-after needs and provide end users with attributes that make their lives more useful and satisfying. Those aspects of a creation may not be apparent at the outset, but they could well emerge as the design process unfolds, revealing themselves as the manifestation gradually comes into being. Indeed, if one were to wonder how a proverbial better mousetrap might arise, this approach to building it would likely reveal how.

This approach proved valuable to Moholy-Nagy not only in devising his finished works, but also in terms of how he ran his school. For example, during World War II, when finances and materials became more scarce, he had to get creative to come up with new ways to acquire both in adequate supplies. Where money was concerned, for instance, he attracted funding by introducing curricula with practical applications, such as camouflage design. He sought to recruit students (and their tuition money), along with additional funding support, to investigate the means for projects like hiding large buildings and even concealing the entire Chicago lakefront. On the materials side, with metal hard to come by because of the war effort, he looked at alternate resources to work with. Consequently, he and his students began experimenting with wood in ways never thought of, such as using it to provide the support mechanisms in bedding.

To succeed at envelope-pushing endeavors like this, we need to push past the limitations in our beliefs that hold us back. This is positively essential for projects where creativity is a core element of the undertaking, because standard approaches aren’t likely to yield anything new, different or innovative. Fortunately, limitations don’t even appear to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s thinking; he stridently forged ahead, apparently not giving a second thought to the restraints of convention. And, for both his benefit (and ours), it’s good that they weren’t part of his process; we can only guess what imaginative manifestations would be missing from our reality today if it had been otherwise.

Thanks to events like museum exhibitions, the work of Moholy-Nagy is finally starting to receive the recognition it deserves, as detailed in the new documentary, “The New Bauhaus,” available for first-run online streaming. Photo by Petter Ringbom, courtesy of Opendox.

Thankfully, this approach to the creative process appears to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s value fulfillment, the conscious creation principle associated with being our best, truest selves for the betterment of our being and that of others. His influence was (and still is) far-reaching, resulting in many creative finished works to be enjoyed, both aesthetically and commercially, as well as inspiring the output of generations of fellow kindred spirits who have since walked in his footsteps. That’s quite a legacy, one whose impact continues to unfold to this day and is likely to continue doing so on into the future.

“The New Bauhaus” is a fitting cinematic tribute to an underrated artist and his work, featuring plenty of examples of his art and that of those he influenced. The film’s extensive archive material shows rare footage of Europe in the days before his immigration, as well as ample still photos from the subject’s time at the New Bauhaus and the School of Design. A wealth of expert commentary is provided by Moholy-Nagy’s daughter, Hattula, along with observations from educators, art curators, historians and former students and quotes from Moholy-Nagy’s writings read by art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist. Aspects of the protagonist’s life chronology could be a little better organized, but the overall portrait painted here provides an in-depth look at the life of someone influential but largely unknown.

As the experience of Moholy-Nagy and his followers illustrates, there is tremendous power and joy in acts of creation. They can take a plethora of forms, too, unfathomably greater than even the phenomenally prolific output of the New Bauhaus and School of Design students and faculty. That in itself should be good cause for the optimism, joy and enthusiasm that came to characterize the attitudes of those enrolled in these remarkable institutions, serving as an uplifting example to the rest of us as we undertake all of our creative endeavors, whether we’re attempting something as ambitious as painting a mural – or simply cooking dinner.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.