‘Honey Boy’ explores the mixed signals behind tough love

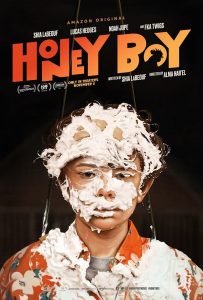

“Honey Boy” (2019). Cast: Shia LaBeouf, Lucas Hedges, Noah Jupe, Byron Bowers, Laura San Giacomo, FKA Twigs, Natasha Lyonne, Clifton Collins Jr., Mario Ponce, Martin Starr. Director: Alma Har’el. Screenplay: Shia LaBeouf. Web site. Trailer.

Growing up under strict parents can be difficult. Their dictates can be a lot to handle, especially when it seems like there’s no getting away from them. And it can be that much more challenging when they dole out seemingly unusual, wholly irrational demands, particularly when combined with questionable behavior and physical abuse. However, as troubling as such conditions may be, sometimes there is a method to that madness, even if it goes unexplained. Such seemingly “tough love” is often misinterpreted as something else entirely, its underlying intent obscured by surface considerations that overshadow what’s behind them. That’s the challenge to be unraveled by a disturbed young adult in the intense new drama, “Honey Boy.”

Set in 2005, “Honey Boy” presents the semi-autobiographical tale of writer-actor Shia LaBeouf’s stormy relationship with his father while growing up as a child star in Hollywood. The story, told through flashbacks to a decade earlier, examines the struggle of now-adult acting prodigy Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges) as he goes through rehab, a requirement to keep him out of prison after several violent skirmishes with the police. During his therapy sessions with his counselor, Dr. Moreno (Laura San Giacomo), Otis reflects back on his upbringing, when his younger self (Noah Jupe) seeks to cope with the many erratic moods and explosive tantrums of his unpredictable father, James (LaBeouf), circumstances that have resulted in a diagnosis of PTSD. Recalling these repressed memories is a painful process, to be sure, but it’s what it takes if Otis ever hopes to recover and set himself on a healthy new path for the future.

Former child star Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges) comes to terms with his troubled past while going through rehab in the new semi-autobiographical film, “Honey Boy.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

As the story unfolds, the elder Otis comes face to face with considerable anguish. He relives his childhood in a rundown motel complex with its many upsetting moments. At the same time, though, he also comes to see that he was the son of a father who generally stuck by him, despite his ample quirks and all through the many difficulties of their volatile relationship. This included Otis’s repeated “failures” in living up to his father’s expectations; their heated disagreement over Otis’s relationship with Tom (Clifton Collins Jr.), a volunteer from the Big Brother program, a protective venture recommended by Otis’s seldom-seen mother (Natasha Lyonne); and Otis’s eventual willingness to fight back and confront his dad on his bullshit, undoubtedly a source of his elder self’s eventual aggressive behavior. The emotional turbulence here was obviously ample and frequent, to be sure.

However, Otis also comes to realize that, no matter how tough James was on him, his dad always seemed to have his best interests at heart, even if it didn’t always appear that way. Having made many mistakes in his own life, James, a former and largely failed rodeo clown, pushes Otis hard in his work, because he recognizes his son’s talent and wants to see him succeed, to not make the same errors that he did. Granted, James’s methods didn’t always work, and he constantly struggled to stay sober after his own recovery, but he was present much of the time in his son’s life. The adult Otis seeks to reconcile these conflicted feelings, learning how to accept – and to forgive – his father for who he was and to thank him what he ultimately did for him.

Many of the themes that pervade this film echo those seen in another recent fact-based drama, “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” (2019). Such topics as forgiveness, redemption and gratitude run through Otis’s story as he seeks to reconcile his feelings with his old man, much as they did for protagonist Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys) with his estranged father, Jerry (Chris Cooper), in “Beautiful Day.” And here, as there, Otis finds his way with a supportive advisor, one who urges him to get in touch with – and to deal with – his feelings, difficult though that may be.

Acting prodigy Otis Lort (Noah Jupe, left) struggles with the many moods and quirks of his father, James (Shia LaBeouf, right), in director Alma Har’el’s latest offering, “Honey Boy.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

The process in both stories involves accessing the beliefs behind those feelings, the driving force in the manifestation of their respective realities. This is important to recognize, for this is the cornerstone principle of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these metaphysical building blocks in constructing the existence we experience. That’s precisely what Otis must do if he, like Lloyd, seeks to understand how and why his world unfolded as it did. It’s essential for him in appreciating how this made him the individual he has become and what he must grasp if he is ever to overcome his PTSD.

Again, like Lloyd, Otis underwent considerable pain, but, as he works his way through it, he also comes to grips with realizing how the experiences of his younger self helped prepare him for adulthood in a career as competitive as Hollywood moviemaking. He admittedly has his issues as a grown-up, but he also has a lot going for him. For instance, would success have come his way if James hadn’t pushed him to work so hard? That’s a question that probably can’t be answered definitively, but we do know for sure that he flourished in his career, in spite of – or perhaps because of – his challenged upbringing. Difficulty often helps to strengthen our tenacity, our willingness to succeed, to become who we were truly meant to be. In situations like that, a change in perspective, including rewritten beliefs about forgiveness, redemption and gratitude, may help us to connect the dots and realize how we became who we are, something for which we may even feel more than a little thankful.

This surprisingly good offering about a talented child star and his troubled father who uses tough love (sometimes a little too tough) to see his son succeed can be difficult to watch at times, given the harshness of his dad’s treatment. Some have also called the film somewhat self-indulgent, an argument not entirely without merit. However, director Alma Har’el’s latest also reveals how situations such as these aren’t necessarily black and white. Inventive cinematography and creative musical montages help to set this one apart from other similar releases, evoking heartfelt but not manipulative emotional responses. Think of this as a grittier, gender-switch, working class version of “Post Cards from the Edge” (1990), and you’ve got the idea what’s behind this one.

Shia LaBeouf delivers a revelatory performance as a character based on his own father in the new semi-autobiographical drama, “Honey Boy.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

Perhaps the greatest strength in this release is its performances. LaBeouf is a revelation, delivering an Independent Spirit Award-nominated supporting performance, one that’s far better than any other he has ever given. He’s backed by two fine portrayals by Hedges and Jupe, also an ISA supporting actor nominee, as well as a Critics Choice Award nominee for best young performer. The film also received additional Independent Spirit Award nods for best director and best screenplay.

Child-rearing receives more scrutiny today than perhaps ever before. Sensitivity to the welfare of kids under the thumb of dictatorial parents definitely deserves the increased attention it has received in recent years, especially for those living under the most vulnerable of circumstances. At the same time, those conditions must be examined carefully, for there may be more than meets the eye in such situations. This is by no means advocating unchecked torment, but, when the true meaning of what’s going on is explored, it may lead to a newfound understanding of what’s transpiring, for both parent and child – an awareness that can lead to the best outcome for all concerned, both during one’s upbringing and on into the future.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment