‘The Feeling of Being Watched’ examines the perils of privacy protection

“The Feeling of Being Watched” (2018). Cast: Interviews, Current Footage and Re-creations: Assia Boundaoui, Rabia Boundaoui, Christina Abraham, Iman Boundaoui, Nouha Boundaoui, Oussama Boundaoui, Sohib Boundaoui, Monica Eva Foster (voice), Daron Hagen (voice), Jen Marlowe (voice). Archive Footage: Donald Trump, Peter Jennings, Nacer Boundaoui, Robert Wright Jr. Director: Assia Boundaoui. Screenplay: Assia Boundaoui. Web site. Trailer.

Many of us likely believe that our personal privacy is a right that we’ve lost. Due to increasingly intrusive surveillance of virtually every aspect of our lives by government agencies, we’ve often come to feel that our personal spaces and individual lives are no longer our own. And, because of explanations like national security and waging the war on terror, those measures have thus been justified by those conducting them. Given all that, it may seem like there’s nothing we can do about it, either. However, one community subjected to severe scrutiny has had enough and has begun to fight back, letting those who are doing the surveilling know that they’re now being surveilled as well, a story chronicled in the troubling but inspiring documentary, “The Feeling of Being Watched.”

When Algerian-American journalist Assia Boundaoui began hearing rumors of long-term government surveillance of Islamic residents in Bridgeview, Illinois, the Chicago suburb where she grew up, she began to investigate. The reporter, whose credentials include work for the BBC, National Public Radio, Al Jazeera, VICE and CNN, was troubled by the prospect, even though many of those around her (including her own mother, Rabia) treated the idea somewhat matter-of-factly, something that they had almost come to take for granted. In fact, when Assia awoke one night and saw what appeared to be a strange vehicle parked across the street, she told Rabia about it who replied “It’s probably just the FBI, go back to sleep.” However, sleep was the last thing on Boundaoui’s mind. If the surveillance rumors were true, this was unacceptable if there was no legitimate reason behind it.

Islamic residents of Bridgeview, Illinois have been surveilled by the government for over a decade in an apparent case of racial and religious profiling, a story examined in the chilling new documentary, “The Feeling of Being Watched.” Photo courtesy of Multitude Films.

Upon looking into the matter, Boundaoui learned that the government launched a surveillance program of the Islamic community in the Chicago suburbs in the wake of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Designated “Operation Vulgar Betrayal,” the FBI investigation looked into the role that Islamic organizations and mosques may have played in funneling funds to terrorists. However, as Boundaoui came to discover, the investigation covered more ground than just the targeted organizations; it appeared to engage in blanket surveillance of the community. And, even though Vulgar Betrayal was shut down in 1999 after allegations of religious discrimination and sexual harassment, it was reopened after the 9/11 attacks – and continued long after.

But to what end? That’s the question Boundaoui wanted answered. By her accounts, most Islamic Bridgeview residents lead everyday ordinary lives, holding jobs, raising families and engaging in all of the other routine activities that American citizens typically do (quite the irony given that many of them are themselves American citizens). So why the widespread scrutiny?

As Boundaoui dug deeper into the story, she began running into roadblocks. Local residents were reluctant to speak about their experiences, even though many of them hinted that they had felt inexplicably targeted. But, to make matters worse, she was stonewalled by officials when she sought information about the investigations. This led to the filing of Freedom of Information Act requests to obtain copies of any documents in the government’s possession regarding its surveillance activities. And what she found out was stunning: The FoIA request responses indicated that the government possessed thousands of pages of information about this subject.

However, when Boundaoui asked for the documents in question, she was told that, due to heavy demand for the fulfillment of pending FoIA requests, it would take several years before she could get the first copies of what she wanted – and even then on a snail’s pace delivery schedule. Such government foot dragging, an obvious stalling tactic, led the journalist to file suit in court. But, even with court rulings in her favor, Assia came up against even more troubling revelations, namely, that her name, as well as the names of her mother and siblings, showed up in the records, despite the fact that the material in the documents overall was 70% redacted.

Algerian-American filmmaker and investigative journalist Assia Boundaoui (right) reviews documents stating that she, her mother Rabia (left) and her brother Oussama (center) were named in secret government surveillance records made available through Freedom of Information Act requests as revealed in the troubling new documentary, “The Feeling of Being Watched.” Photo courtesy of Multitude Films.

Suddenly, the investigation turned personal, a troubling thought for a journalist trying to maintain a sense of objectivity. Boundaoui now found herself having to walk a tightrope between uncovering the truth and addressing her own personal privacy concerns. Was the revelation of her name in the documents a government intimidation tactic because of the aggressiveness of her investigation? Or were she and her family part of the ongoing surveillance all along simply because of their Islamic faith? Indeed, were the Boundaouis caught up in a broad-spectrum program of racial and religious profiling with no legitimate justification?

These revelations thus raised the question, where do Bridgeview residents go from here? And is this government surveillance effort limited to just the Chicago suburbs? What is the Islamic community to do?

That’s where this film comes in. In her directorial debut, Boundaoui is blowing the whistle on what has been occurring. She has been taking the documentary to her people, making them aware of what’s going on and encouraging activism to expose the truth. In essence, she has put the government on notice to let the watchers know that they are now being watched.

Efforts like those undertaken by Assia Boundaoui are truly courageous. That’s not to say that such initiatives aren’t scary, but the intrepid journalist and her supporters have not let that hold them back. They have taken their story to Islamic community centers and mosques to spread the word, building a broad base of support and awareness.

In unraveling the story behind government surveillance of the Islamic residents of Bridgeview, Illinois, filmmaker and investigative reporter Assia Boundaoui reviews thousands of pages of documents in “The Feeling of Being Watched.” Photo courtesy of Multitude Films.

This kind of effort is a prime example of the conscious creation process in action, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. Even if the activists aren’t aware of this philosophy, their actions – and results – illustrate their proficiency at making use of this practice. By getting past their fears and holding a clear vision of what they hope to achieve, they’re making great progress in letting others know what’s going on behind the scenes.

This effort is crucial not only for the protection of the rights of the American Islamic community but for all Americans. After all, if this can happen in one segment of society that is placed under scrutiny, it’s not out of the realm of probability that it can happen to others as well. One need only look at the experience of immigrants coming from other lands these days to see how easy it is to be put under an investigatory microscope – whether it’s warranted or not.

It’s somewhat ironic that the watchers are now being watched, too. After all, as conscious creation maintains, our outer world is a reflection of our inner realm, and, if the watchers believe that they must engage in such surveillance, then it shouldn’t come as any surprise to have their tactic turned back on them. Their efforts are, fittingly, now being mirrored at them, validating that what goes around truly can come around, for better or worse.

Making the Islamic community aware about covert government surveillance is one of the aims of filmmaker and investigative journalist Assia Boundaoui (left) as chronicled in the revealing new documentary, “The Feeling of Being Watched.” Photo courtesy of Multitude Films.

Those who are being unfairly surveilled need a voice to speak for them, and that’s precisely what’s being accomplished by this excellent documentary. It’s a chilling story about a courageous advocate’s efforts to expose a troubling issue and how she has had to balance her coverage of a story that affects her both professionally and personally. Boundaoui’s meticulous storytelling details everything that went into the unraveling of this mystery, showing how she followed an ominous trail of breadcrumbs that led her to where she is now. This is must-see viewing for anyone who feels his or her privacy is threatened – or could be.

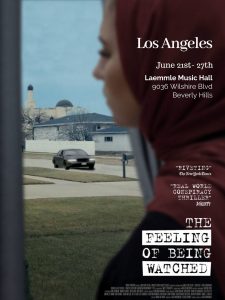

“The Feeling of Being Watched” may take a little effort to see, at least in the near term. It has been playing at film festivals, in a limited theatrical run, and at special screenings at mosques and Islamic community centers. In October, however, the film will receive national coverage when it airs on PBS. It should also be noted that this film is a work in progress, one that will be updated as further developments in this story unfold. Viewers should thus be on the lookout for new information as events transpire.

It’s stunning how so many of us have taken the loss of privacy in stride. Something so cherished should be jealously protected, given that it may be difficult to retrieve once it’s gone. In that regard, this film should serve as a wake-up call to those who take this precious freedom for granted. When any of us lose this, it’s a loss for all of us, a true tragedy for a nation that was built on such a formidable and fundamental principle.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment